When NPR commentator, author, husband and father Ben Mattlin was 3 years old, he fell from his new wheelchair as his father pushed it down a steep ramp. Because of his amyotonia — as spinal muscular atrophy was known when he was a young child — Mattlin, now 50, likened himself to a rag doll, unable to keep from rolling down the ramp. Mattlin later saw his mother lecture his shaken father about using the wheelchair’s seatbelt. His mother then turned to her young son, urging him to also remind caregivers to fasten that belt.

When NPR commentator, author, husband and father Ben Mattlin was 3 years old, he fell from his new wheelchair as his father pushed it down a steep ramp. Because of his amyotonia — as spinal muscular atrophy was known when he was a young child — Mattlin, now 50, likened himself to a rag doll, unable to keep from rolling down the ramp. Mattlin later saw his mother lecture his shaken father about using the wheelchair’s seatbelt. His mother then turned to her young son, urging him to also remind caregivers to fasten that belt.

“I try to take her admonitions as seriously as I can,” Mattlin writes. “Speak up. Don’t be shy… I hear these phrases a lot. Light a candle instead of cursing the darkness.” Mattlin understood the message, but also realized his wonderful new wheelchair “brings a host of unforeseen risks and burdens. Everything is double-edged! … I’m not yet four, but I might as well be 40.”

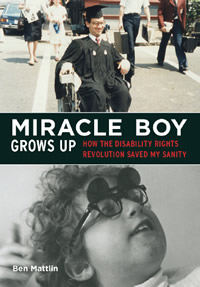

Published in August, Mattlin’s book, Miracle Boy Grows Up: How the Disability Rights Revolution Saved My Sanity is more than Mattlin’s personal story. It’s also a history of how accessibility rights came of age in America. Mattlin was growing up at the same time that his country was working to comply — often not very enthusiastically — with accessibility legislation such as the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Those growing pains, along with Mattlin’s own experiences, changed his perceptions of the world, of people with disabilities, and of himself.

In his book, Mattlin dismisses his lifelong resilience as simple necessity, and shares anecdotes and experiences that fall decidedly on the opposite side of sainthood. As a child, Mattlin fantasized about being a superhero, but he works hard in his memoir to prove he is just an ordinary guy who, as the saying goes, has lived in interesting times. Calling on a sharp wit and a gift for language — he discovered early on how powerful his words could be — Mattlin declares in the book’s introduction that he is simply telling the truth. If we happen to be inspired by his story, he adds with a presumed wink, that’s our problem. It’s a problem I suff ered repeatedly while reading Miracle Boy.

In his book, Mattlin dismisses his lifelong resilience as simple necessity, and shares anecdotes and experiences that fall decidedly on the opposite side of sainthood. As a child, Mattlin fantasized about being a superhero, but he works hard in his memoir to prove he is just an ordinary guy who, as the saying goes, has lived in interesting times. Calling on a sharp wit and a gift for language — he discovered early on how powerful his words could be — Mattlin declares in the book’s introduction that he is simply telling the truth. If we happen to be inspired by his story, he adds with a presumed wink, that’s our problem. It’s a problem I suff ered repeatedly while reading Miracle Boy.